In this edition: marches, explanations, imaginings, enactings. I started writing parts of this one back in February, and it’s been waiting for me ever since.

It’s the 16th of November. This morning I wake up to an email from the Charlestown Electoral Office in Newcastle, informing me that I’ve been removed from the Overseas Electors list due to a lapse in my eligibility. I knew it was coming. They’ve twigged, finally. I did debate, briefly, retelling the lie that “I intend to live in Australia within the next six years”, once a year, for the foreseeable future, and decided I didn’t want to. It feels stranger and stranger to vote in a country I’m becoming a stranger to. Still, it does kind of suck to read about your personal political disenfranchisement, bleary-eyed in the grey light of a Berlin November day.

I wonder if I’ve voted in my last election, I think.

I spent this last Saturday evening gathering signatures for a campaign to compel the city of Berlin to enact policies – especially energy policies – to become climate neutral by 2030. Es ist nicht zu spät, the lurid green and red placards have been informing us for weeks. It’s not too late. My signature doesn’t count, since I’m not a citizen of the EU. The deadline was on Monday, and if they’ve gathered enough signatures that do count, then there should be a referendum in the next election. So far, it looks good – they overshot the amount they estimated they’d need by more than 20,000 signatures.

It’s a critical moment, for multiple reasons. Everyone’s thinking about energy right now. The why of it all slips out of mind a lot though. While Annie was visiting from the States a couple months back she said something like, “with the war going on now and everything,” and my first thought was, which war? Nonetheless, we’ve been wondering all year how winter will be, and it’s finally arrived. My flatmate and I have barely turned on the heating so far, although it’s getting to the stage where that’s not really optional anymore. I walked into the bathroom after she took a shower last night, and the warmth from the radiator was almost shocking. It hits my brain in the following sequence:

Warm. Is it off? It’s off. We have to keep the heating off, because – and then my brain fills with overlapping images of placards, of banners, of marches, of pipelines, of tanks, of rubble, of burning forests, and it’s all sitting on top of each other until it gently blends into static noise, and I placidly pick up my toothbrush.

The message comes over the train speaker system: they won’t let us off the train at the Brandenburger Tor station, it’s already too full of people. We get off at Potsdamer Platz instead. I say we, but I’m on my own here, dressed in yellow and blue, wearing a crown of tiny yellow and blue foam flowers Sonja brought back for me from her trip to Ukraine years ago. I didn’t text anyone, didn’t try and meet up – I just got dressed and left the house, heading north.

As I walk towards the crowds, a man stops me to ask when the demonstration is beginning. “It’s starting now,” I say. And when will it end? I shrug – “No idea.”

It is eerie to walk past the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe today. It is the 27th of February 2022, it’s very sunny, and there’s a war underway. But then, there’s always a war underway.

There isn’t a good sense of direction once I get to the Brandenburger Tor. Supposedly there was going to be a “peace chain” from the Ukrainian Embassy to the Russian Embassy, but that hasn’t materialised. Some people are drifting towards the Russian Embassy further down Unter den Linden, but mostly people are walking away from it, through the gates and into the Tiergarten. I loop around past the Hotel Adlon, cross towards the European Commission, and start following the crowd.

Most people are wearing FFP2 masks and walking a little bit apart from one another, but I can still pick out conversations of people around me. Two women in their sixties chat about going to the sauna just as we pass under the shadow of the Gate – “You really need the whole day, there are so many good treatments and infusions, you can really spend so many hours there.”

Someone carries a sign imploring the government to spend more on weapons. “I’ll pay more taxes,” it reads, “spend more on the military!”

Before I left home that morning, I got a text from Rosie, who was watching the news in Sydney.

I clicked around until I found the Deutsche Welle feed she was watching. She caught me up – “Lots of money into green power, plans in place for financial supplements into the future when prices get fucked due to the war, contributing weapons… they raised the defence investment to above 2% and everyone went nuts clapping.”

Once Scholz and Merz were finished speaking, the feed cut to analysts talking about the speeches. Germany has entered “a new era” with this policy, they said. Defence spending has been a famously touchy subject for the German federal budget, for Germany’s relationship with its NATO allies, for Germany as part of Europe, but this conflict has changed everything.

At the demonstration, three girls near me make plans: “When do you want to go home? I’ll need the bathroom soon, so maybe another hour, hour and a half.”

Voices come over the shaky sound systems, and someone is talking about the need for solidarity that actually costs us something. There are hard “ch” sounds in the speaker’s German, which rattle out across the street. I tune in to the sounds, asking my brain to focus and translate as I listen. “The blood that will be spilled in war screams to heaven, and God hears this scream.” People laugh nervously, and look at one another over their masks. There is scattered clapping as the speech comes to a close.

We are walking past the Soviet War Memorial, toward the Siegessäule, away from the Brandenburger Tor. Each of these monuments is a complicated symbol of war, conflict, uneasy resolution, unification, dissolution. One girl asks her friend in English why the street we’re walking along is called Street of the 17th of June.

“Was that date the liberation from the DDR?”

“No, it was an uprising at the beginning of the DDR, in 1953.”

They move on; next to them someone holds up a sign painted in psychedelic colours and shapes: “Drop Acid Not Bombs”.

The Brandenburger Tor was originally called the Friedenstor, or “Peace Gate”, to emphasise rebuilding the country after various conflicts Prussia was involved in towards the end of the 18th century. The Siegessäule (or “Victory Column”) is a monument to Prussian victory in the Second Schleswig War with Denmark in 1864, some 70 or so years later – a war whose battlegrounds I lived amongst for five years, in Flensburg. The Soviet War Memorial is dedicated to both Ukrainian and Russian soldiers who died here. Despite what the girl near me asked her friend, there wasn’t exactly a “liberation” from the DDR. There was a reunification. A peaceful end to a long, tense conflict. It took 28 years for the Wall to come down. We’d walked over its ghost just two hundred metres behind us. Nobody dropped bombs on the Wall, they tore it down gleefully and now you can buy little painted pieces of concrete pretending to be the Wall in tacky souvenir shops.

I hold all these facts up next to each other in my brain and look at them, one by one, reshuffling them. I put one foot in front of the other. The crowd is so quiet, I think. Even with the loudspeakers, it’s shockingly quiet here. I’ve been to so many demonstrations in these streets, in this country. Usually there’s chanting, usually there’s more talking, but people aren’t chatting as much now.

Over the loudspeakers, a different voice – a politician from the Greens party – says, “The past belongs to gas, oil and coal. The future belongs to sun and wind!” Germany is one of the largest importers of Russian natural gas. Everyone claps for that. Someone has a sign that says, “Democracy and freedom are worth it – better to freeze than get oil from Putin!”

We’re coming slowly to a standstill. It’s too crowded now. The voice on the loudspeaker says, “Hello, you five hundred thousand!” There is a small cheer – too small for so many people. A sign nearby says, “War is only Poland away.” It’s impossible to move down the road in either direction, and there’s a fence running along the edge of the Tiergarten’s trees and bushes. I watch two people clamber over it, and then follow them myself. I can’t get any purchase on the steel trellis with my shoes, so my hands and thighs take the brunt of my ineptitude as I slide over. Once in the gardens, there is at least room to breathe, though there are still people everywhere. I start heading back towards Potsdamer Platz, when the voice on the loudspeaker calls for a minute’s silence.

Almost everyone stops where they are, and those who keep moving glide past on the edge of the paths. There is noise, but it’s far away – traffic many blocks from here, birds, distant children’s voices. I look at the snowdrops near my feet and wonder if I’m about to cry.

After the minute is over, I text Polina. I send her a photo of me walking through the gardens, wearing the crown. She says all sorts of people have been emailing her and getting in touch. She tells me she’s going to the demonstration in Flensburg, that it feels like she’s going to a funeral.

It is very sad

I feel very sad

And helpless,

she writes. Her family had a place in Crimea. This is new, and not-new.

We exchange in-jokes about the work we used to do together, until we’re both laughing to the point of tears – she in Flensburg, me in Berlin. She thanks me for going to the march. She tells me she loves me. I tell her I love her too.

It is August. J.S.1 and I are at brunch, and it’s raining. He’s been telling me about the summer camp he’s just been working at, and now we’re throwing ideas back and forth about significant societal change, idly, in the way you do over brunch. There’s something very soothing about talking about revolution over a platter of things, and German brunch is 90% platter-based.

He says, “I imagine something like a game the kids love at camp, where you throw a ball around a circle until someone in the middle – wearing a blindfold – says ‘bomb’, and then it ‘explodes’.”

“Right,” I say, listening, but also deciding which cheese to eat next.

“So I imagine people walking around this city, with like a bomb appearing over their head for a while, and then disappearing as it moves to another person, and another, until finally someone says ‘bomb’, and then I guess that person will lead the revolution.”

“Horrifying,” I say, picking up a cherry tomato. “That would mean we might actually have to do something. Like, take decisive action.”

“And you’d just never know when the bomb was hovering over your head,” he adds. “It could be there any time.”

I wonder, briefly, if we do know. We’ve just been talking about the responsibilities we take on in trying to build safer spaces on a small scale, and then expanding them. The anxieties around our own anticipated failings. The endless yawning unknown unknowns. Maybe they’re the first faint outline of that invisible image, flashing into being above us.

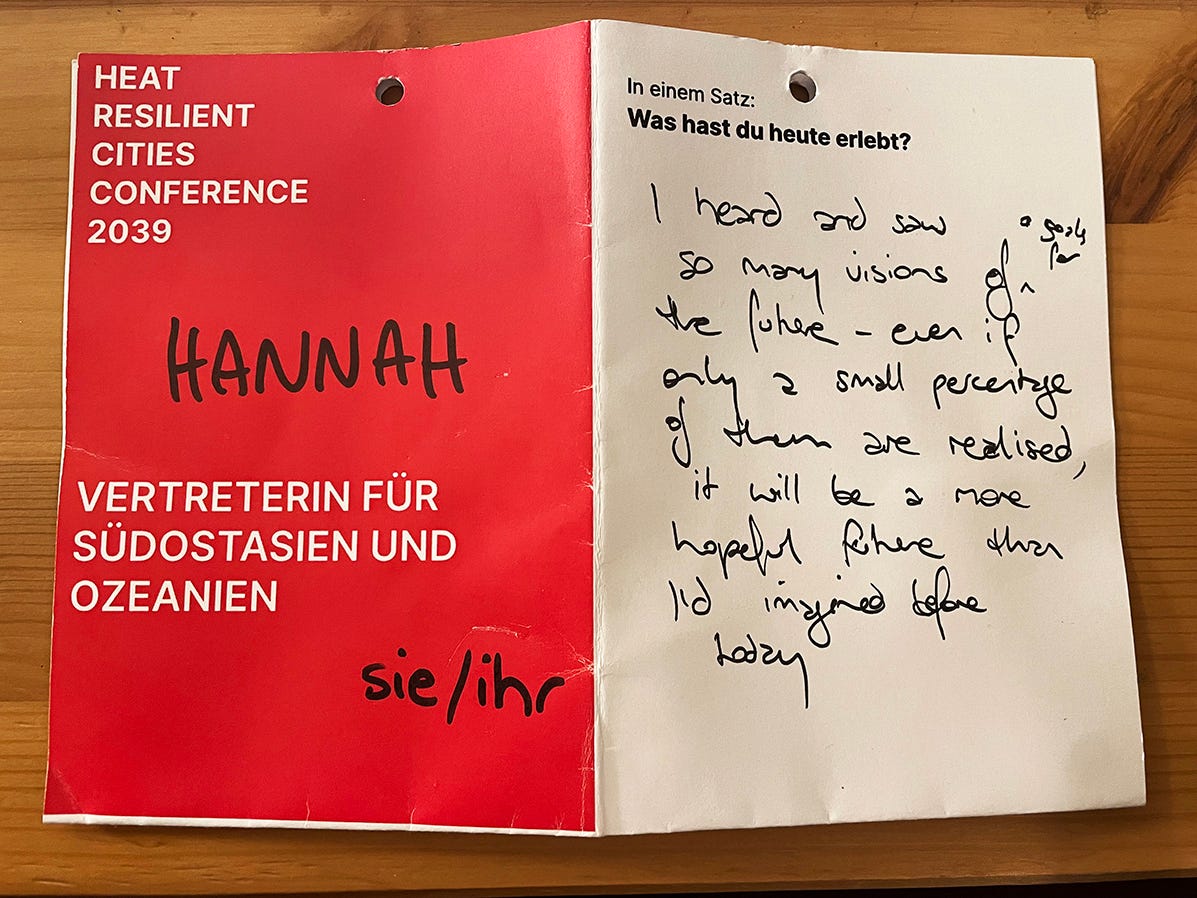

It is October. Juli asks me if I’d be interested in helping her create characters for the 2039 Heat Resilient Cities Conference, and yes I absolutely would be, so she and John and I spend the next couple of days dreaming up the civically engaged citizens of Berlin, twenty years from now. Her project is amazing to me: an immersive imagining of an apocalyptic future with utopian policy outcomes. Basically, on the day of the conference we will all sit in a room together, playing characters in 2039 who’ve lived and worked through unprecedented climate disasters (a task that, Juli notes, becomes easier with each passing year) and who are reflecting on all that’s happened in the past ten years since the horrifying heatwaves of 2029. We will talk about how the district of Neukölln has transformed, with public space orienting itself around the urgent need for cooler spaces, and the economy and political structure shifting towards more sustainable practices like co-ops, shared decision-making, communal living.

She and her teammates have run several conferences in the past, but this is the first one where the characters are designed in advance. The three of us sit in their living room, laptops open to spreadsheets, building out ideas. John begins each new brainstorm the same way: “Close your eyes. Okay, so imagine, you wake up in the morning, you brush your teeth, and you’re a…” In our real, 2022 lives, the participants are researchers, scientists, designers, activists, artists. In our 2039 lives, we are small business owners, local politicians, community organisers, urban planners, heads of committees and organisations. And often also researchers, scientists, designers, activists, artists. We invent new political positions, create local networks of supply chains, dream up backstories based in pandemic-era life shifts that we see happening around us.

It is October 2022, and it is also October 2039. I am Caitlin, but I am also Hannah, who is also an Australian expat, and shares a lot of biographical details with Caitlin.

Hannah remembers volunteering in the cooling tents that were hastily thrown up in Hasenheide, the big park down the road, and the chaos and improvisation and good will and sheer audacity that was required to make things work in the early days of responding to the heat crisis – the knowledge-sharing on first aid, the distribution of those suffering from heat sickness throughout different tents. Caitlin remembers spending two nights at Südkreuz station in the first weekend of March, watching buses bearing Ukrainians come in from Poland between 2am and 6am and handing out tea and soup and SIM cards, and feeling so awake and so present and so awed at how everything is so well-organised and so fundamentally unorganised all at once. Hannah remembers getting heat-sick herself after a few weeks, and having to stop. Caitlin remembers how she told everyone she was going to start volunteering again when she got back from Australia, and then didn’t.

Hannah sees people she remembers meeting back at the early days of the Hitze-Hilfswerk (“We must have met… I guess it must have been 2030, right? Or 2031? I think I wasn’t working as a coordinator yet, and they couldn’t hold the conference that year, so it must have been…”). Caitlin is enjoying the small moments of world-building that happen one-on-one (“Remember how Elon Musk accidentally blew himself up in a rocket on the way to Mars and all his wealth was redistributed? Yeah, what a time that was.”). As both – as either – I am struck over and over by how collectively imagining something makes that imagining feel so real, by the power given to another person’s suggestion or idea by saying “yes, and”, imparting weight and form and location in the world.

John is quiet all day. When we get the chance to talk about it, he tells me his character, Tim, a soon-to-retire tech worker for a big company, doesn’t seem to have a clear role in the world we created for everyone else, doesn’t seem to have much expertise to contribute to this new system created in the midst of disaster. We worked a lot on everyone else’s characters, and our own remained outlines – we thought we’d have enough background to draw on without thinking through all our motivations and backstories. But some things grate too close to the surface of our fears and frustrations. I hit my own crisis point in the reflection session over Zoom, two weeks later.

“But I don’t know who needs to know all this,” I say, “I don’t know who gets to make the decisions where all these things actually happen. It feels like we need a catastrophe to happen in order for anything to change, or we need someone to decide to do things differently for other reasons, and I don’t know who that someone is!” I think about myself, a supposed political sociologist who can’t even vote in an election in the place she lives in – or, soon, anywhere at all. “I don’t even know enough about the German political system to understand how that happens!”

Everyone else in the session has been through this before. They’ve had this discussion. Juli speaks up. “It’s not really one person, though, in reality there’s not just a few people who can make the decisions to change systems like this.”

Which is something I’ve known all along, I suppose, but it’s a lesson I have to keep learning.

Hey there friends. Tell me what you think by replying to this email, or tell everyone what you think in the comments:

If you want to get more of these on an unreliable timeline in your inbox, you can, and it’s free!

J.S.’s name is Julian, but not the same Julian I usually refer to as Julian in this newsletter; I have been hoisted by the petard of my own writing conventions and a need for more variety in the name pool of my friends, alas, alas. Maybe I should have given everyone fake names, but I’m almost two years (!) too late for that bright idea.

Beautiful to witness this weaving dance of personal and political, social and spiritual