In this edition: time, urgency, and healing (or something like it). This is the third and final installment in the Mouse series, and deals with grief, death, trauma, animal suffering and death, anxiety and dissociation. If those topics are too difficult today, then file this one away for “read later”, or gently relegate it to the land of forgotten emails. Here’s Part I, and here’s Part II.

Early October, 2023. We are sitting on the train platform in the evening rain, waiting to head back to Berlin.

“I keep thinking, like, what if something happens to my parents. Like what if they die, and I don’t know?” John’s staring out at the industrial yard across the tracks.

I exhale deeply through my nose. “I guess that is the gamble we make, living so far away.” I’d asked him if he’d thought about moving back to the States, a question that struck a shrill, frightened bell in my brain.

“But that’s the question, right, like what difference does it make if three days pass before I find out they’ve died? Does that make a difference?”

I don’t know. I don’t know what it means for time to pass between the thing that happens, and the knowledge of it hitting your brain. I sort of know what it feels like, it’s happened before, but sort of – more distantly. To people I hadn’t spoken to in a while. “How do you think it would feel?” I ask him.

“I don’t know,” he says.

There’s no blood, or anything so obvious, on my hands, but I keep them stretched away from me anyway. “Okay, it’s done.” What if it was sick. What if I get sick. “I’m gonna not lift that concrete again, I’m going to do myself the service of not looking at -”

“Yeah no don’t. Don’t.” John is looking at me, and then he’s not-looking at me. “This is so so horrible. It should have just been a nice walk.” We’re moving over towards the path, and he’s saying it like he has to pin the feeling down.

I’m hoping the concrete will deter any scavengers for just long enough. It’s like a tombstone, I think, a grave covering. I have not seen the mouse, I will not see the mouse. “It is, but now we have to get our hands clean. Deal with the dangerous thing first.”

“And you had to do this today, when -”

“Yeah, but that dissociative thing my brain does? This is what that’s for,” I say, realising it as the words come out of my mouth. “This is when it’s doing it’s job right.” I’m going to pay for this, later.

I want to be held, I want to be reassured, but any contact feels dangerous because I held the mouse, because I wanted to reassure it. Soft. I don’t know how to meet John’s eyes. Max is still very quiet. I lead the way down the hill, focused. With each step, I notice the way my brain feels.

Calm, I think. I feel calm. I feel clear, like a sheet of perspex.

There is soap in the little shop by the rose garden, when we ask for it. People are lining up cheerfully for ice creams and we hover ghoulishly nearby, holding our hands away from our bodies like haunted mannequins. I follow John into the men’s bathrooms, where the water in the sinks is a cold blade on my skin. I rinse my hands twice. It’s still not really enough.

But at least I can look at the other two, now. I come out of the low pebblecrete building shaking my hands, and they watch me approach. I am calm, I am not calm, I know this isn’t normal.

August 2023. Moon is sitting with me in a café, a fast food restaurant, it is lunchtime, it is nearly midnight, we are on the street eating hot chips and she’s saying:

“Amygdalic time. Everything is either right now, or never.”

The lighting is weird, the café-street-restaurant-living-room laid on top of one another, she’s saying:

“Your brain can’t tell that time passes, when it’s stressed enough in this way.”

There is clarity: it is 1am, the salt from the chips stings my lips, I say, “I’m just afraid that things will break somehow, and be left – like they are now. It feels like someone’s dying.”

She sighs. “In the unlikely event a meteorite strikes Sonnenallee tonight then there’s not much you can do. But that’s not actually what’s happening, things will change. You will get the chance to say what you need to.”

And then we’re in the café by the bridge, and she’s saying, “If it seems like something is really, really urgent, but there’s not clear evidence as to why, that’s usually exactly when I know I need to slow right the fuck down and wait.”

Amygdalic time. We’re pretty sure Moon coined the term. The way the brain collapses everything together in order to be able to deal with too much. The brain filtering out the axis of time in order to deal with what is and isn’t important. Moreso than any physical bodily sensation, it’s that part of anxiety and panic attacks that brings on the conviction that I’m dying: the notion that this exact moment absolutely requires action but there’s not a clear thing to be done, like maybe something could be done, here’s a list of twenty things I’m not sure about and can’t prioritise, nothing feels definitely like a sure thing, maybe I should do something drastic, and actually maybe it’s just because someone else should be doing something, why aren’t they doing it, don’t they realise that every passing moment is absolutely catastrophic?

In the midst of this fog, I write:

Patient

1st August 2023

They say time heals all wounds

As though time were the surgeon and not the recovery bed

As though time were the scalpel and not the anaesthetic

As though time were the salve and not the oxygen,

breathed involuntarily,

absorbed without intent.

A waiting room is not a healing place,

As anyone who has sat in one knows.

It is for the unspecified,

The undiagnosed,

The time where all horrors are possible and yet to come,

Including the worst, where they cannot find a source for the malaise

And tell you that you ought to be fine.

Wait and see,

Take two to six more weeks,

Enough time to forget how difficult it is to secure an appointment

Enough time for your schedule to fill up

With matters of seductive importance and sublime distraction.

At what point does patience become palliative?

The membrane that holds back the poison has a half-life

And the other half is spent waiting for it to finally decay

Can you really call that living?

Ah, my love, there is nothing more lifelike -

The eternal compromise

Of time spent trying to earn more time

Darling, I need you to hear this:

Like any medicine, time will kill you if you take too much,

And we are all prescribed a lethal dose.

Without action, our manifestos become eulogies:

You are going to have to start digging inwards now,

Or into the cold earth before too long.

There’s a truck selling beverages near the entrance to Tempelhofer Feld, so we grab some lemonades. I still don’t really want to touch things with my hands, which feel volatile, hazardous, but I take the bottle of pineapple lime – the last one in the fridge – and open it.

“To the mouse.” Clink.

I keep replaying moments in my head – John’s shoulders dropping in defeat, the mouse in the dirt, the duct tape on its tail, the concrete on the ground – and then, others, the phone in my hand, fire police ambulance?, the flashing lights, pacing along the beachfront, along a carpark four storeys up, the garage door closing, the pen in the hand of a uniformed cop. That’s what that part of my brain is for. That’s its job. I realise I didn’t want anyone else to kill the mouse. I had to do it. I had said the words, and I had to make them real.

We sit on the bollards at the top of the hill. Max says, pensively,

“My sister and I found a baby bird once, that had fallen out of its nest. We tried to find a way to put it back in, but it was too high, and we couldn’t just leave it on the pavement. We tried to take care of it.”

I am listening, mostly, but the words bounce off memories, Mum saying just a few weeks back, Remember that bird you tried to save, that you found on your way home from school? I wonder how many people have a dying bird story.

Every story is also a hundred other stories.

“It was when the sun went down at the Chime & Oak festival,” I say to Moon. “I was having a great time, it was such a nice day and everything was easy, and then suddenly I was on high alert as soon as it got dark. My heart was racing for no reason, and I couldn’t stop thinking about last year.”

The bulb in the café/restaurant/streetlight buzzes softly. Last year, there’d been a crisis, after the festival ended. The street, the steps, the phone in hand, the indecision. The need for action.

“Isn’t it incredible, how the mind works?” Moon says. “That’s your brain pointing out patterns. It’s capable of such subtle analysis and recognition – it knows that all of these elements, this event, this place, this time of day, has led to a situation where you needed to be alert, and that eventually led to danger.”

“Feels like a bug, not a feature,” I reply.

“But now you have more resources to deal with that situation, starting with the knowledge that certain elements lead to stressful circumstances. Maybe not in this case, but – your brain is trying to help you, it’s trying to protect you.”

The body is always trying to protect me, somehow.

It’s been two weeks since the surgery, and the pain has shifted somehow, subtly. I wonder if I’ve just overdone it, going for walks, shuffling along at a demonstration, trying to weave myself back into the world. But there’s blood, and something else, and I go to a doctor, who sends me immediately to the hospital.

Ferdi comes with me, plays word games with me for distraction, and then Hamza arrives to keep me company. We sit in the waiting room for five hours.

“I swear I’ve been here sometime in the last few years,” says Hamza, “I just can’t remember the context.”

“Once when I was here in 2020, a man in a bed next to me had a seizure and fell to the ground, bleeding. Nobody came, I had to go searching for someone to help,” I tell him, flooded with sudden memory.

My body has learned where to be alert, but it has a harder time with healing. The surgery has resulted in complications. It will require another surgery. Maybe if we keep cutting, over and over, the flesh will find a way to re-form itself without creating hollow, dangerous caverns or fragile tissue.

The weeks of recovery have felt like a dangerous cavern, a dark pocket out of time and life in which I need to offer up, over and over, any sense of control or understanding or composure. My friends have seen me past the limits of vulnerability I’d previously thought possible, which leads me to the suspicion that there’s probably far greater depths of trust and helplessness that one could explore if one were not absolutely fucking terrified by the very prospect.

Lisa voice notes me, reaching straight into my chest through my phone. I know what a challenge it is for you not only to admit that you need help, but also to ask people for it. So to ask people for help for this length of time is as you said, beyond anything you were anticipating. But what I will say is, I one hundred percent guarantee that none of your friends are looking at it that way. No-one’s thinking, fucking hell, this is taking ages, they’re thinking how can I continue to help, what can I do. I briefly entertain the thought of what it would mean to need this kind of help for months, or years, or decades, and my mind abruptly shuts the whole thing down.

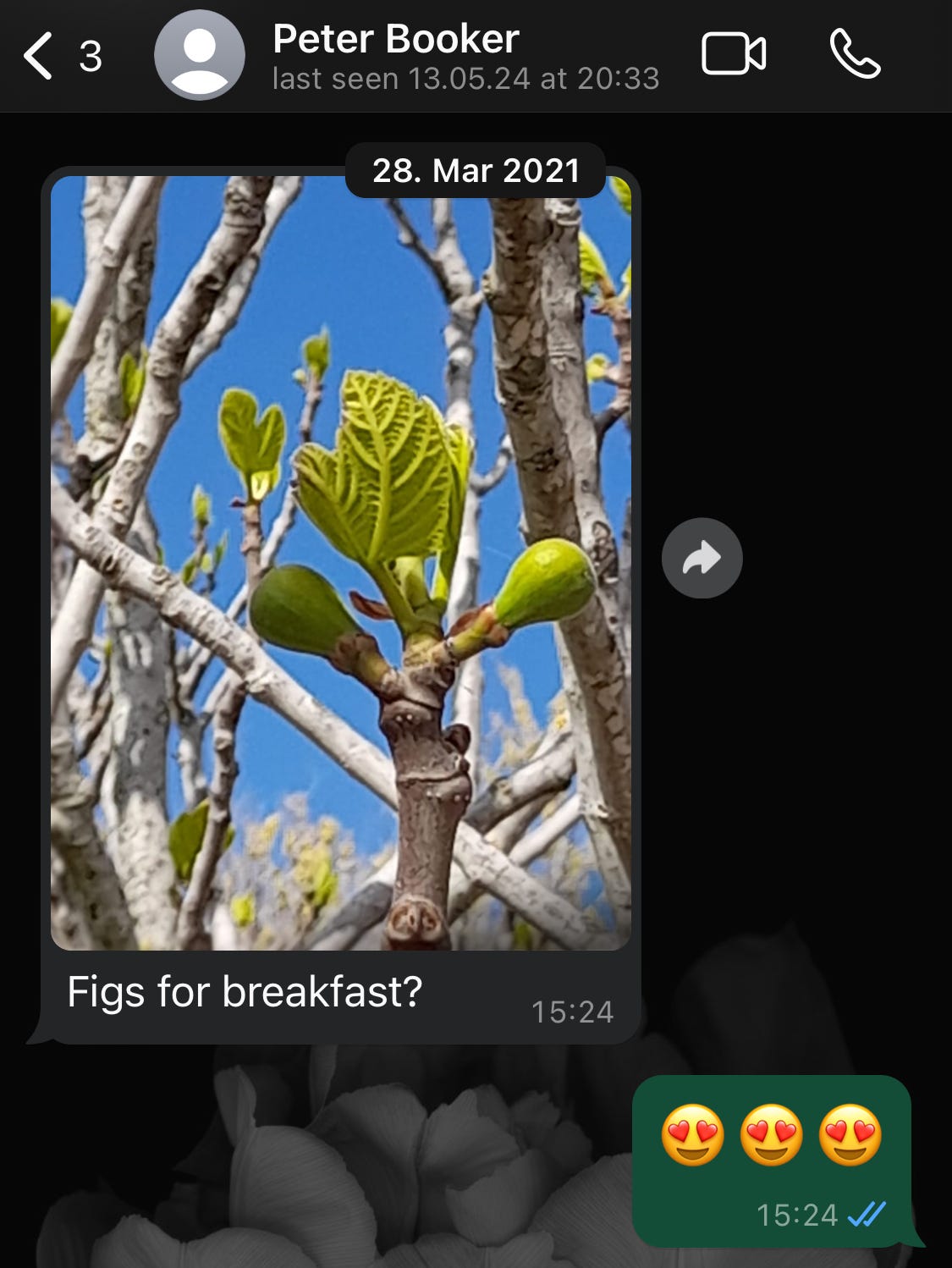

Peter looks at me earnestly over his wine glass, the lights of the town twinkling in the distance behind him. “But really, you know, the thing they say about family is true. They’ll be there for you, you can count on them no matter how many years have passed, no matter what kind of distance, you can always ask them for help. It’s something so precious.”

I sigh. Peter is perhaps the person who is closest to me that still struggles with my decision to cut off contact with my father, his cousin. He still talks endlessly about the relatives he thinks I should know, even though I’m sure they wouldn’t recognise me any more than I’d recognise them.

“Family is a relationship I choose to be in with people. It’s always made more sense to me to understand family as those who decide to be part of my life in that way, rather than just by default because we share genealogy,” I tell him, and take his hand. “We’re family, we’re closer than most first-cousins-once-removed I guess, but that’s because we have actually put time and energy into being family. Those are the kinds of relationships I need in my life, the ones I value.”

He squeezes my hand. “Well, you know, you’re the daughter I never had, really, and I want you to know you can always count on us. Especially living all the way over here, it’s hard.”

“It’s not as hard as it was to live there,” I say.

The next day, I’m playing love songs on my ukulele on the little terrace outside my room. Peter, listening, says, “You should bring more of your friends here. To visit. It sounds like you have a lot of really special friends.”

The sun is starting to sink towards the airport buildings on Tempelhofer Feld, the ripening light rippling across the runways towards us. This is where, the first time John and I met up more than two years ago, we sat and listened to the sounds of the Feld after a long talk about our jobs, our curiosities, our friends, our fears. Do you want to do a meditation exercise? he’d asked me. Uh, yes! I’d responded. Okay, we’re going to choose a number between one and five, and that’ll tell us which noises we’re going to listen to – one is right up close to your body, and five is far away in the city. We’re sitting on almost the exact same bollards.

I’m going to spend the next three weeks checking my WhatsApp chat with Peter, to see if he’s been online. Last seen today at 9:58. I’m going to think about sending another message, to tell him more, to tell him everything I can think of, to tell him as much as I can fit into thirty minutes, and thirty minutes after that. He’ll still be alive, as far as I know. He’s still alive as long as I don’t know any different. It would still be possible to tell him. I won’t ask anyone how he’s doing. I will just wait, in that strange between-space.

And when he’s gone, I want to go tell the bees in the garden. I’ll tell Arielle, in tears on the day I find out, I wanted to go tell the bees, but I can’t walk right now. They’ll reply, The bees can wait, they’ll still be there. You’ve got time.

Right now, I just close my eyes and try to isolate different sounds at different distances. The dog park is a three. The traffic is a five. The clink of the empty glass bottle on concrete is a two. Max and John are both quiet, their silence a two. The mouse never made a sound at all.

My breath, in and out, is a one. The sound of the blackbirds, a three, maybe a four. It is warm behind my eyelids, a shimmering gold. I turn to John next to me, and I’m about to say pick a number between one and five, but before I can open my mouth he says, “Shall we go?”

And we go.

Here we are, at the end of this series. I’m out of the hospital as of this morning; I don’t know yet if the second surgery was successful, but it sure was Another Experience™, especially on my birthday (which I decided to postpone indefinitely, but still felt sad about). Some of these stories have been waiting in my drafts a long time, some are still unfolding as I write. I’d like to send something a bit lighter and sweeter to you all soon, if my brain and body allow.

Until then, if you feel like it, you can reply to this email or, indeed,

And you can look into these links to support those facing the unimaginable in Gaza and in Palestine more generally:

Operation Olive Branch

Donate an eSIM

Donate to the PCRF

Donate to UNRWA

Join local demonstrations, take a friend - for those in Germany, one great source is Jüdische Stimme für Frieden. Demand an end to the genocide, demand liberation.

If you’re not already getting Figs in your inbox, here’s where you can

for no money at all.

You truly have some amazing friends/chosen family. Loved the writing. Thank you for sharing.

Get well soon. Fingers are crossed that the surgery went well this time.